Globalisation has dramatically increased

translation volumes. Thanks to the internet, even SMEs employing just a few

people are muscling into the global market, generating more and more text to be

translated. Since machine translation does not produce convincing results, the

number of translators should likewise be skyrocketing. But this is not the

case. How, then, can relatively few translators handle this ever-growing volume

of text?

Recycling based on fuzzy logic

The invention of the translation memory

(TM) has shaken to the core traditional translation, with its steadfast

reliance on huge dictionaries, an approach virtually unchanged since Babylonian

times. Translation memories are based on the human predilection for repetitive

behaviour. Many companies and organisations continue implementing similar

processes over and over again, for years, saying pretty much the same thing every

time. TMs are optimal tools for hoovering up the resulting 'corporate speak' –

which, statistically speaking, always consists of the same blurb. These little

miracle workers operate on the basis of fuzzy logic, which can recognise

variable language patterns. As a result, the costs involved in translating a

company CEO's annual Christmas speech which changes relatively little on each

occasion can be cut year on year.

The first commercial translation memories

were produced in Stuttgart. In the late 1980s, Jochen Hummel and Iko

Knyphausen, a couple of technology geeks who had set up a small translation

agency in 1984, started developing various programs to support the translation

process, also referred to as Computer-Aided Translation – or CAT – tools.

The system is really simple: individual translated text segments are stored

together with the source text in a database to form a parallel corpus. If

Trados, as this now world-famous software is known, recognises a block of text,

or elements of it, the memory recycles the relevant translation from the

memory. In ideal cases, translators will then only need to confirm the

suggested translation, speeding up their work. CAT tools can generate

significant savings in repetitive texts. If car manufacturer Citroën has

already produced manuals for its C2, C3, C4 and C5 models, the translation of

its C8 manual will cost a lot less.

The biggest advantage of TMs is invisible:

they make a company's language consistent, harmonising its documentation, sales

and support material and website. This way, everything becomes straightforward

and uniform. The first globally successful 'orgy of harmonisation' came in 1997

when Microsoft sought to simplify the translation of its operating system into

all the world's major languages as much as possible. Bill Gates quickly bought

up part of Trados, optimised the system and made Windows the most successful

software of all time. Dell and other large customers followed suit. In 2005,

the company was snapped up by British competitor SDL, which took over the

'Trados' brand name for its software products.

From standalone solutions to cloud-based TMs

The vast majority of translators work from

home as freelancers. But until recently, high-speed data lines were more the

exception than the rule. Out of necessity, individual translators created their

own databases, resulting in a myriad of standalone solutions. They saw their

databases as their own private property, so it was hard to motivate them to

cooperate. The big agencies responded with forced collectivisation by creating

a new job, namely that of 'translation manager'. The translation manager's job

was to act a bit like a tax collector, demanding the submission of bilingual

files after every assignment. From that time on, translators and revisers

received packages with each order, containing all the key translation resources

they needed. The results then had to be returned, again as a package, which the

translation manager fed into the main memory.

Smart agencies were able to build up

enormous memories and consolidate their market position. However, their

diligence was undermined by an inherent flaw in the system: the larger the main

memory became, the worse the quality of the packages. The 'concordance memory'

and the glossaries, which by this stage were gigantic, were too big to fit into

the package, placing individual freelancers at a serious disadvantage, compared

with server users.

In 2015, SDL, the company which had taken

over the Trados software, launched the first usable GroupShare server. Since

then, blocks of text have been stored on a central server, so that any number

of translators can access these translation resources. This server technology

means there is now no limit to the recycling of translation segments. And from

here it is just a small step to 'World Translation', a cloud-based TM

containing every translated segment on the internet.

The digital revolution as a cost killer

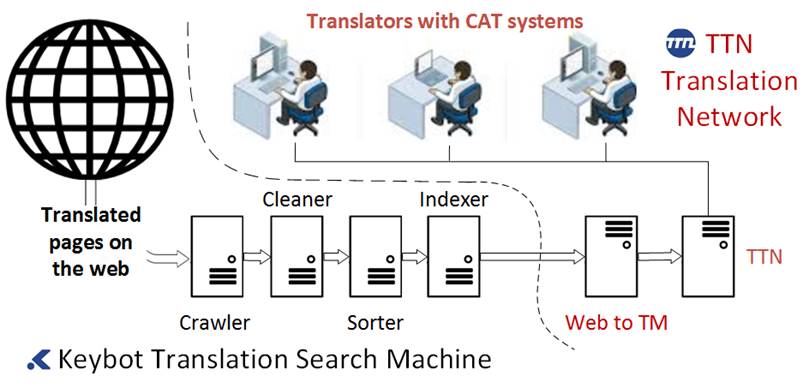

The blueprint for the first fully

automatic translation network, called the TTN Translation Network, was drawn up

in Geneva in 1987, before the internet as we know it existed. TTN's founder,

Martin Bächtold, trialled the first inter-university networks at Stanford

University in Silicon Valley. The lectures he attended detailed the comparative

advantage model, making it immediately obvious that translation and

communication would henceforth go hand in hand. The idea was that future

translations would be produced in regions offering the best price-quality

ratio, where the target language was actively spoken.

When Martin flew back to Geneva, his

luggage contained one of the very first modems. Using this loudly-hissing tin

box, which was still banned in Switzerland at the time, the world's first

translation server was installed on a Schnyder PC with a 10-Mb hard drive. But

this innovation came far too early for the market. Back then, nobody knew how a

modem worked. The company had to borrow money to buy devices on the cheap in

Taiwan which it then shipped free of charge to its customers and translators.

One of its first customers was the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and

Landscape Research (WSL) avalanche warning service, an offshoot of the

Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research (SLF) in Davos. Avalanche warnings

had to be translated very fast, with the resulting texts sent back in digital

format, not by fax. Back then, when an avalanche bulletin arrived, translators

were informed by loud fax warnings, a system long since replaced by text

messages and smartphone interfaces.

Created at CERN in Geneva in 1989, the

World Wide Web revolutionised communication technology by introducing a new

standard. When TTN went online, the Swiss Post Office at the time assigned it

the customer number 16. Profits from the first system were ploughed into

the development of a kind of ARPANET for translations in India, where a huge IT

team programmed the code. The idea was to use a replicated network to establish

a cloud system capable of fully automatically routing 165 languages. This

attempt ended in failure, because the code was overly long and the problems

encountered proved far more complex than anticipated.

The second attempt was more successful,

but took much longer than expected. Step by step, ever larger parts of the

processes were automated, slashing production costs by 30%. It turns out that

agencies using artificial intelligence can manage large customer portfolios

more efficiently than their exclusively human counterparts. Their programs

calculate translators' availability, taking into account their working hours

and holiday absences. And this optimised time management benefits translators,

who enjoy a more constant stream of work. In a nutshell, there is less stress

and greater productivity.

|

|

|

High levels of computational power

required

Patrick Boulmier, Big

Data specialiste from Infologo in Geneva is working with Keybot CEO Martin

Bächtold to ready the very latest supercomputers for this 'world language

machine'. The aim is to convert hundreds of websites a minute into TMs.

|

|

Keybot: Web to TM

Many global multinationals take a

haphazard approach to the digitalisation of translations. While these companies

have web applications with thousands of translated pages, they have no

translation memories with these texts neatly stored in parallel corpora. This

lackadaisical approach to selecting a translation provider has disastrous

consequences: specifically, when poorly organised companies set out to overhaul

their website, they have to pay the full price for every page, because the work

already done cannot be recycled. As a result, a lot of knowledge is being

unnecessarily lost, and reacquiring it costs money.

'Web to TM' entails

combing the internet and converting it into an enormous translation memory:

This gives such companies a helping hand.

Keybot, a TTN subsidiary, has developed a translation search engine of the same

name which scans the internet in a similar way to Google. But it only stores

multilingual pages, indexing them as parallel corpora. A complex network of

servers mines the data and searches potential customers' websites for

translated text segments. The extracted knowledge, i.e. the 'big data', has to

be cleaned and sorted and then subjected to statistical analysis. Repetitions

have to be counted and their significance calculated and recorded. Only when

this laborious process is complete can the machine pass on the information,

piece by piece, to a battery of GroupShare servers. After this long, drawn-out

procedure, whenever translators open an order with their CAT software, all the

parts the search engine has found on the customer's web application will have

been translated automatically. The translator always has the latest version to

be published, not an outdated version subsequently edited in-house.

To enable Keybot to match elements of

language, it inputs all Wikipedia pages and translations of biblical texts and

human rights in 165 languages. Each language has its own 'genetic code' that

can be extracted in the form of n-grams. Keybot tries to use these statistical

properties to identify and create parallel texts out of these blocks of text.

The system is still at the beta stage, and so far it has only been possible to

create reliable TMs if a customer has structured its website in such a way that

the crawler does not get confused during the input process. The largest-ever

translation memory so far generated was produced for a US firm and covers 23 languages.

Keybot intends to transform the entire

multilingual part of the internet into a gigantic translation memory. 'Web to

TM' is the way ahead. This transformation will be highly intensive in

computational terms, so can only be performed by a correspondingly huge server

farm. To acquire the necessary capital, Keybot is planning an IPO on Germany's

SME exchange and is trying to raise crowdfunding to finance some of the

hardware.

SLOTT Translation

The decisive innovations in machine

translation were prompted by the meteorological sector. Weather forecasts face

a virtually insoluble dilemma: they have to be disseminated rapidly, but must

contain no translation errors. The statistical approach adopted by Google

Translate doesn't help in this regard, as it is too inaccurate and can never

hope to reproduce the ultra-precise nature of weather warnings.

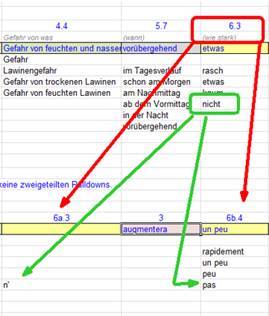

Jörg Kachelmann, a really smart weatherman

who had studied mathematics in Zurich, was the first person to resolve this

dilemma. He took a simple Excel sheet and put together a cell-based system

capable of managing language generation. As far back as the 1980s, the head of

the SLF tried, but failed, to build a machine translation system. A German

university's statistical attempt harnessing the principle of probability and

Markov models also failed to deliver. So years later, when Kurt Winkler, an SLF

engineer based in Davos, sent a bizarre-looking Excel sheet from the Alps to

that language metropolis, Geneva, at first linguists ridiculed him as the 'fool

on the hill' and his project was banished to their bottom drawer, like some

second-rate detective novel. It was only when he persisted that a TTN employee

familiar with translation memories was given the task of checking the integrity

of Winkler's solution. One incorrect sentence, and Winkler's system would have

been dead and buried.

After

three days, there was still no word from this TTN analyst. Amazingly, no errors

were found, and even a program specially designed to elicit them was unable to

detect any. Winkler, who knew nothing about linguistics, analysed the texts of

weather alerts and their translations for the previous 10 years, based on

potential mutations. The fruit of his efforts was an Excel database that nobody

could understand.

Or COULD they? A century ago in his

lectures, Geneva-born Ferdinand de Saussure, the founding father of

Structuralism, had highlighted the syntagmatic structure of language. He was

the first to define the potential mutations that could occur in a linguistic

structure, though he did not spot the connection with other languages. Winkler

broke down the texts into segments using the same principles and set

transformational rules for translating text segments from one language into

another.

|

Dr. Kurt Winkler

|

|

Machine translations for greater

security

This was

how the SLF's Dr Kurt Winkler made an amazing breakthrough in machine

translation, enabling avalanche warnings to be translated in a fraction of a

second.

|

|

Bizarre-looking

Excel sheet

|

Using Winkler's catalogue of standard

phrases, millions of idiomatically and grammatically correct sentences can be

generated in four languages. However, his system only works for avalanche

warnings in Switzerland, and the phrases need to be generated using an

on-screen catalogue. This is not very practical and its application is

extremely limited.

TTN is experimenting with an analogue

system, known as SLOTT Translation. As with weather forecasts, the translations

must not contain any language errors, as this would undermine customers' faith

in the system. In future, communications with customers will be standardised

using a catalogue of only 20 sample sentences, so that enquiries can be

correctly answered in flawless language.

It is unclear whether SLOTT will be able

to gain a foothold as a commercial system. However, there is no doubt that

future TMs will be hierarchically organised, significantly enhancing their

potential. So the next generation of CAT systems will be able to properly

translate not just the exact text stored in a TM, but also millions of

variants.

Free for

publication (2337 words)

Martin Bächtold, Keybot LLC, Geneva, May 2017